If you’ve ever thrown a dinner party, you know cooking for guests can be a logistical challenge. Imagine cooking for 500,000. That is the task faced by the volunteer chefs and chai wallahs at Amritsar’s Golden Temple, the Sikh religion’s holiest site, on Guru Nanak Jayanti, which celebrates the birth of Sikhism’s founder.

The langar, or community kitchen, at the Golden Temple serves free food to anyone who visits the glimmering shrine, from pilgrims to tourists to locals in need of a hot meal. On on average weekday, about 80,000 people eat in the langar; on weekends, close to double that figure. But on Guru Nanak Jayanti, an estimated half million diners descend on the langar.

Every 15 minutes, a new group of diners enters one of the langar’s vast halls. They take a seat on one of the mats laid out in neat rows and watch as their steel thalis are loaded up with dal, vegetables and rotis by one of the many volunteers constantly marching down the aisles looking for plates to refill. After eating their fill, diners toss their plates and bowls at metal shield-wielding volunteers who deflect them into buckets bound for washing.

It is a well orchestrated process from the frying of the first cumin seed to the washing of the last spoon. Perhaps the most celebrated cogs in the langar’s wheel are the roti machines, which buzz every day turning 12 tons of atta flour into roughly a quarter million perfectly round flatbreads the size of small frisbees. Custom-built for the langar, these humming hunks of steel are contraptions that would make Rube Goldberg proud, taking the flour on a transformative journey through a mixer, a roller, and down a ten-yard conveyor belt of fire before popping out as a piping hot piece of bread.

But it is the volunteer chefs who embody the spirit of the Golden Temple. Volunteers come from all castes and communities to perform seva, or service, in a kitchen the size of an airport hangar, where massive cauldrons bubble with lentils and onions are stacked eye-high in mini-mountains.

Sukhpreet Singh, 20, a computer science student from Amritsar, has been doing seva at the Golden Temple since childhood when he would pour water for diners alongside his father. After he turned 18, he started coming on his own every Saturday evening from 7 pm til 2 am. His role is now one of the langar’s most important – he is the Golden Temple’s chai wallah.

Sukhpreet is matter-of-fact about the significance of his job. “It’s just as important as making food. Guests come and they want tea. In Punjab, we are friendliest to our guests. Whatever they want we give them.”

Sukhpreet says he does not know how long the Golden Temple has been serving tea, but acknowledges it was likely not served in the 16th century when Guru Amar Das, the third Sikh guru, institutionalized the langar as an element of every gurdwara, or Sikh temple.

“The Britishers brought tea to India. Before that we drank milk. But now we cannot do without tea.”

Tea is served in an open patio outside the langar where people pour themselves bowls of chai from converted water troughs. They are free to go back for as many refills as they like. Should they need a cup of tea upon coming or going, volunteers hand out steel cups of chai and rusk biscuits in the walkway outside the Golden Temple.

The langar’s manager, Harpreet Singh, said he expected 30,000 cups of tea to be served per hour on Guru Nanak Jayanti. Sukhpreet would have to prepare chai the night before and it would not be a one-man job, so he brought along six friends to work with him.

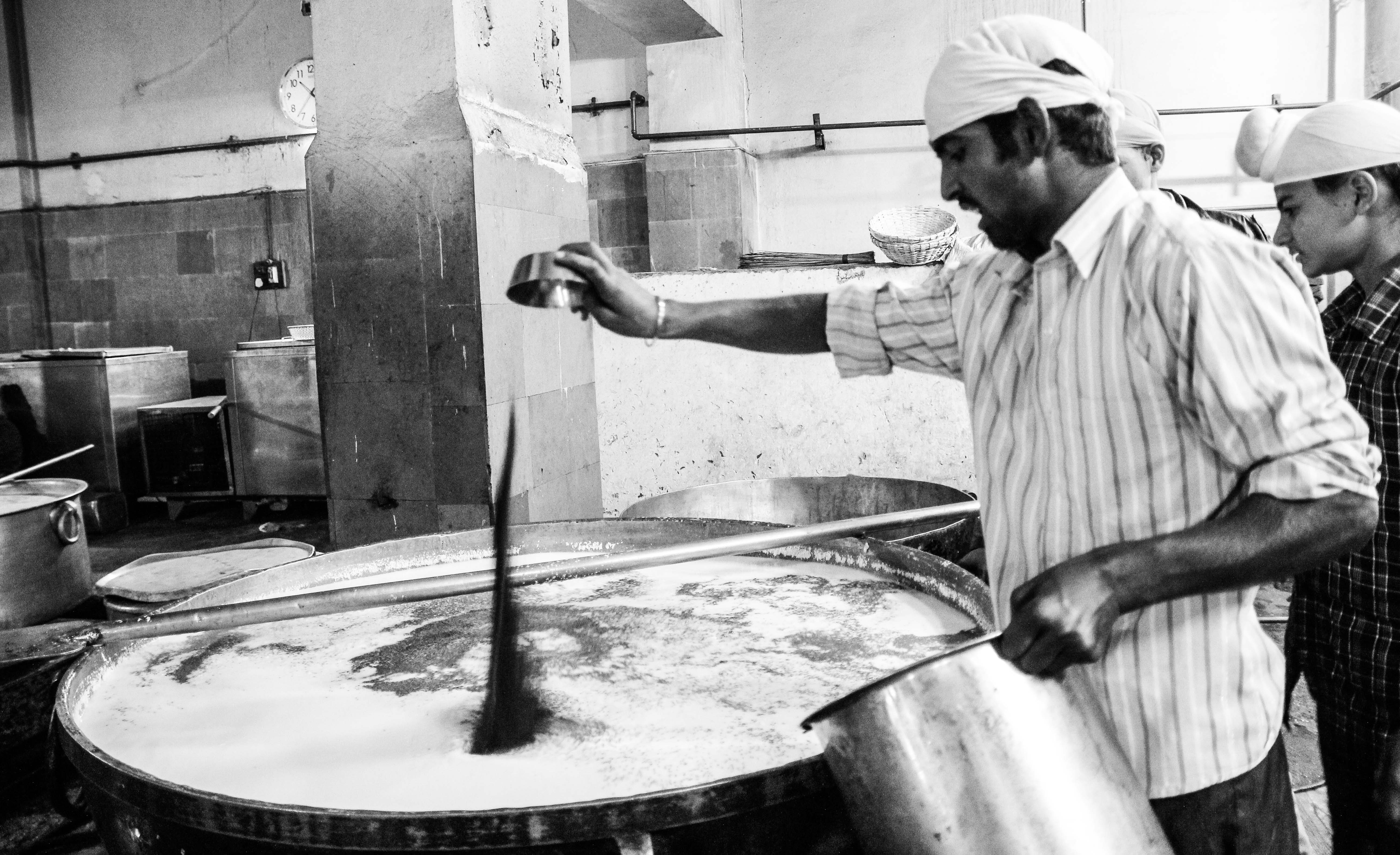

The seven erstwhile chai wallahs make seven cauldrons of chai – each the size of a hotel hot tub. For each cauldron, they begin by diluting 30 kilograms of dry milk powder in 300 liters of water poured in from what appeared to be a fire hose.

That process takes about 30 minutes, according to Sukhpreet. “You have to pour in the water a little bit at a time, get it hot, mix some milk, then do it again.”

When the milk is ready, two of Sukhpreet’s friends dump in 50 kilograms of sugar from steel tins. An hour later they dump in about two kilograms of CTC tea pellets and half a kilo of a masala mix donated by a local spice merchant containing cinnamon, fennel, ginger, ajwain, and two types of cardamom – big black badi elaichi and small green choti elaichi.

The volunteer chai wallahs let the mixture boil for four hours, occasionally stirring the chai with a spatula reminiscent of a pole used to clean a pool. At the end of the night they will transfer the chai into vessels from which it will be served.

“We are here doing God’s work,” says Sukhpreet as he loads one of the vessels onto a handcart. Proving his point is a passage written above the entrance to the langar from the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikhs’ holy book: “The Lord Himself He cooks, Himself He places it on the platter, and Himself He eats it too.”